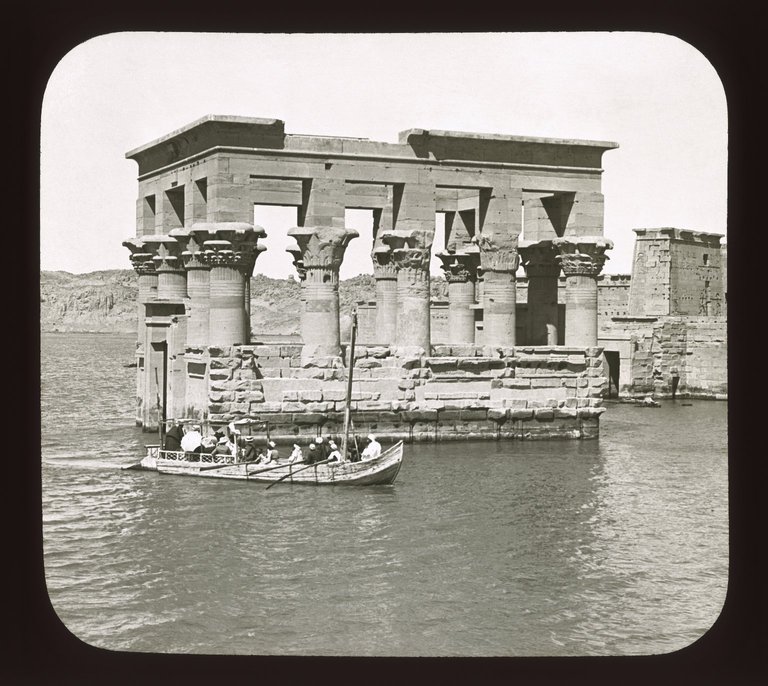

Long before the relocation of Philae, the temple would get flooded, especially in times of a high inundation levels. Travellers would sail through the temples in boats, which is very evident in their inscriptions high up on some of the columns. The temple and the island of Philae have been a source of wonder for millennia; Philae is mentioned by numerous ancient writers, including Strabo, Diodorus, Prolemy, Seneca, and Pliny the Elder.

They would not be the last of the travellers to marvel at its wonders.

Of all the islands, temples, and ruins strewn along the Nile in the deserts of Egypt, Philae would always garner the most attention of all ancient travellers. Victorian travellers went through great lengths in describing the ambiance, serenity, and the grandeur of the temples of Philae and their vivid reliefs and carvings—the ones that survived mutilation by overzealous early Christians and Iconoclasts

Another intrepid Victorian lady traveller to Egypt was Lady Lucie Duff-Gordon (1821–1869), described as “an intellectual, traveller, writer and progressive social commentator.” She was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1862, and went to live in Egypt on the advice of her doctor, where she later died in 1869. She settled in Luxor, learned Arabic, “and immersed herself in the Egyptian way of life”. [Source: Lucie Duff Gordon: A Passage to Egypt (Tauris Parke Paperback)].

Lucie wrote many letters to her husband and her mother about her observation of Egyptian culture, religion and customs, these letters were later published in 1902 by her daughter. She spent two nights in Philae in May 1864. Her views, while more progressive than those of her peers, are still in many ways typical Orientalist views of Arabs in general, and Muslims in particular. And as with most Europeans had a dislike of the Ottoman Empire.

I have left her letter intact, with no editing, as a window into the past.

We spent two days and nights at Philæ and Wallahy! it was hot. The basalt rocks which enclose the river all round the island were burning. Sally and I slept in the Osiris chamber, on the roof of the temple, on our air-beds. Omar lay across the doorway to guard us, and Arthur and his Copt, with the well-bred sailor Ramadan, were sent to bivouac on the Pylon. Ramadan took the hareem under his special and most respectful charge, and waited on us devotedly, but never raised his eyes to our faces, or spoke till spoken to. Philæ is six or seven miles from Assouan, and we went on donkeys through the beautiful Shellaleeh (the village of the cataract), and the noble place of tombs of Assouan. Great was the amazement of everyone at seeing Europeans so out of season; we were like swallows in January to them. I could not sleep for the heat in the room, and threw on an abbayeh (cloak) and went and lay on the parapet of the temple. What a night! What a lovely view! The stars gave as much light as the moon in Europe, and all but the cataract was still as death and glowing hot, and the palm-trees were more graceful and dreamy than ever. Then Omar woke, and came and sat at my feet, and rubbed them, and sang a song of a Turkish slave. I said, ‘Do not rub my feet, oh brother—that is not fit for thee’ (because it is below the dignity of a free Muslim altogether to touch shoes or feet), but he sang in his song, ‘The slave of the Turk may be set free by money, but how shall one be ransomed who has been paid for by kind actions and sweet words?’ Then the day broke deep crimson, and I went down and bathed in the Nile, and saw the girls on the island opposite in their summer fashions, consisting of a leathern fringe round their slender hips—divinely graceful—bearing huge saucer-shaped baskets of corn on their stately young heads; and I went up and sat at the end of the colonnade looking up into Ethiopia, and dreamed dreams of ‘Him who sleeps in Philæ,’ until the great Amun Ra kissed my northern face too hotly, and drove me into the temple to breakfast, and coffee, and pipes, and kief. And in the evening three little naked Nubians rowed us about for two or three hours on the glorious river in a boat made of thousands of bits of wood, each a foot long; and between whiles they jumped overboard and disappeared, and came up on the other side of the boat. Assouan was full of Turkish soldiers, who came and took away our donkeys, and stared at our faces most irreligiously. I did not go on shore at Kom Ombos or El Kab, only at Edfou, where we spent the day in the temple; and at Esneh, where we tried to buy sugar, tobacco, etc., and found nothing at all, though Esneh is a chef-lieu, with a Moudir. It is only in winter that anything is to be got for the travellers. We had to ask the Nazir in Edfou to order a man to sell us charcoal. People do without sugar, and smoke green tobacco, and eat beans, etc., etc. Soon we must do likewise, for our stores are nearly exhausted. Letters from Egypt: Lady Duff Gordon’s Letters from Egypt

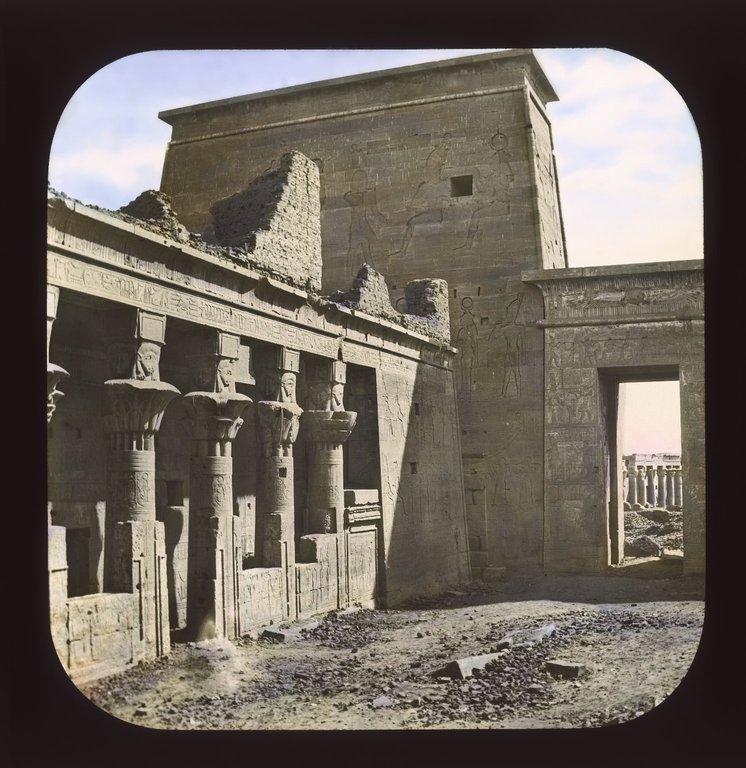

Egypt: Temple of Isis in Philae, capitals of the east colonnade by Brooklyn Museum, taken sometime in 1900.

Egypt: Tourists on a boat ride next to the submerged Trajan’s Kiosk; Philae was regularly flooded by the Nile’s inundation, by Brooklyn Museum, taken some time in 1900.