From the moment the mighty river enters Egypt, it travels approximately 1,000 miles / 1,609 kilometres till it reaches its final destination, the Mediterranean. Without the Nile, there would not be Egypt, the Pyramids, Karnak, or any of the massive monuments that we see today. Egypt would have been just a part of the great Sahara.

In ancient times, Egypt was mostly ruled from the south, specifically from what we now call Luxor. Sadly the importance of Upper Egypt waned through millennia, and power shifted from the South all the way to the Delta and Alexandria, to finally settle in Cairo. That is the main reason for the wealth of archaeological sites and finds in the south of Egypt and along the Nile Valley.

Life hasn’t changed much here, farmers still farm the same way their ancestors did, they still use the same names for the same tools, villages have had the same names for hundreds of years.

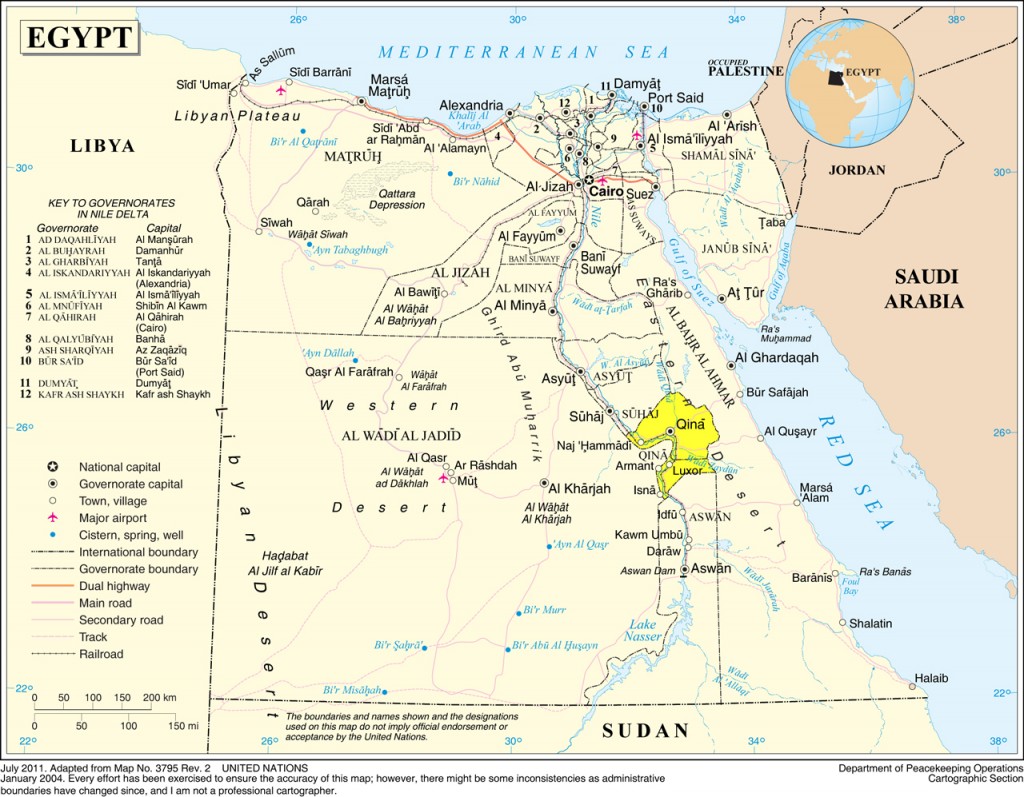

Due to the size and number of governorates along the Nile Valley, this guide is going to be split into three parts: 1) Middle Egypt; 2) Qena and Luxor; 3) Aswan and Nubia.

Qena

About 500km to the south of Cairo is Qena, while it lacks in Luxor glamour, it still has some gems enough to make you wander off for a while. Named after its largest city and capital, it was known as Kaine during the Greco-Roman period and as Cainepolis in antiquity.

It is home to several very important sites in antiquity: Naja’ Hammadi, Dandara, Naqada, and Qus, each with their own claim to fame.

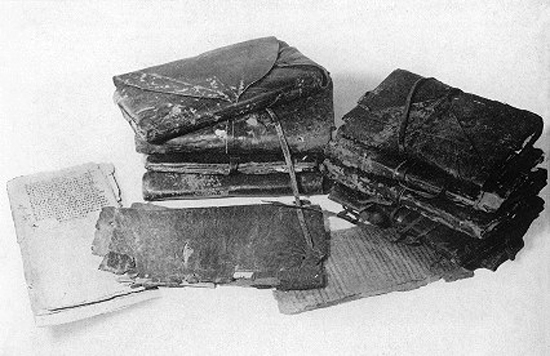

Naja’ Hammadi is where the Gnostic Gospels were discovered back in 1945, they are also known as the Nag Hammadi Codices. In December 1945, a set of 52 religious and philosophical texts, hidden in an earthenware jar for 1,600 years, was accidentally unearthed. Not far from the village of Naja’ Hammadi in Upper Egypt, two brothers came across an entire collection of books written in Coptic, a discovery that would be explosive to the historical and theological communities. This corpus of 1,200 pages is currently conserved at the Coptic Museum in Cairo and contains one text in particular that made the headlines – the Gospel according to Thomas, which was originally called ‘the secret words of Jesus written by Thomas’. Source. Source.

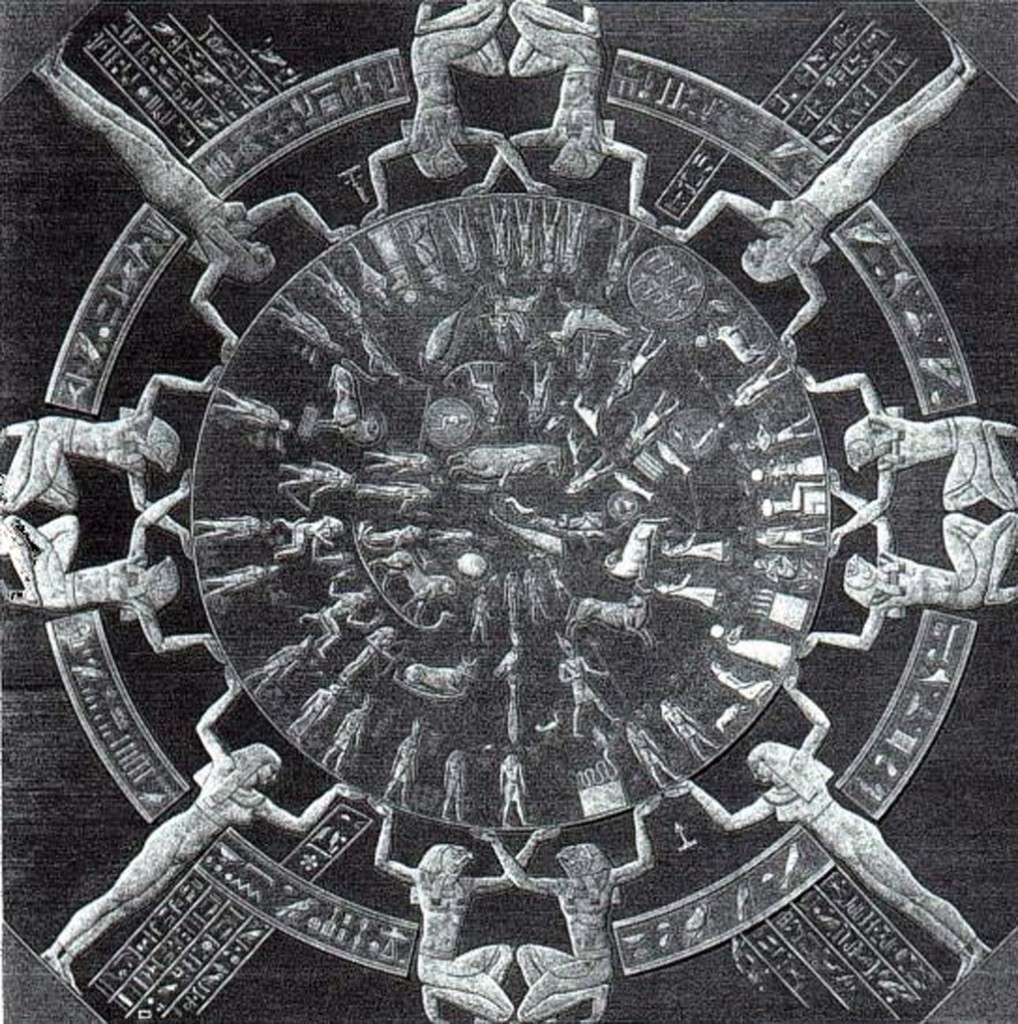

Dandara and Qena lie north and south of each other across the Nile – due to the Qena bend. Dandara is the site of the Dandara Temple Complex which contains the Temple of Hathor, one of the best preserved temples, if not the best, in all Egypt. The complex’ total area is about 40,000 m2 and is enclosed within a large mud brick wall. The present building dates back to the times of the Ptolemaic dynasty and was completed by the Roman emperor Tiberius, but it rests on the foundations of earlier buildings dating back at least as far as Khufu – Cheops, second king of the 4th dynasty, in which was found the celebrated zodiac now in Paris; there are also the Roman and pharaonic Mammisi (birth houses), ruins of a Coptic church and a small chapel dedicated to Isis, of the Roman or Ptolemaic epoch. Source.

Qift and Qus (from ancient Egyptian Gebtu and Gesa) were the crossing point to the Red Sea and the Eastern Desert in ancient times, Qift has the remains of three temple groups surrounded by an enclosure wall that were located during the excavations of W. M. Flinders Petrie in 1893-1894, and later, by Raymond Weill and Adolphe Joseph Reinach in 1910-1911. In the 13th century with the opening of an alternate commercial route to the Red Sea, Qus replaced Qift as the primary commercial centre for trading with Africa, India, and Arabia. As such, it became the second most important Islamic city in medieval Egypt, after Cairo.

Further south on the west bank of the Nile is the small town of Naqada. It stands near the site of a necropolis from the prehistoric, pre-dynastic period around 4400-3000 BCE. Naqada has given its name to the widespread Naqada culture that existed at the time: Naqada I and Naqada II. However, most come here to see the massive Pigeon Palace built by a monk just over a century ago; the mud brick Qasr Al-Hamam enables 10,000 birds to recuperate from their flight over the Western Desert and food is always available.

Luxor

The jewel in the crown of ancient Egyptian archaeology: Luxor. Its name is driven from Al-Uqsur (the palaces). It lies about 635km south of Cairo, and it was separated from Qena in 2009 and made into a governorate, and had the towns of Armant and Esna (Greek: Hermonthis and Latopolis) annexed to its boundaries. Luxor is all about Ancient Egypt, so do not expect to see any significant Coptic or Islamic monuments.

The world’s greatest open air museum, Luxor, was dubbed “a city with a hundred gates” by Homer in his Iliad. Known to the Greeks as Thebes, its importance started as early as the 11th Dynasty, when it became renowned for its high social status and luxury, and as a centre for wisdom, art, religious and political supremacy. Thebes played a major role in expelling the invading forces of the Hyksos from Upper Egypt, and from the time of the 18th Dynasty through to the 20th Dynasty, the city had risen as the major political, religious and military capital of Ancient Egypt.

Luxor boasts a massive concentration of antiquities, including the stupendous Karnak Temple Complex built over 1300 years, the grand Luxor Temple, and the Theban Necropolis. Each of these areas needs a separate article just to cover its history and splendour. Luxor also houses two museums; the Luxor museum and the mummification museum.

Here are some interesting facts about two of the major sites within Luxor: 1) when the invading French army under Napoleon first sighted Luxor Temple in 1799 they spontaneously presented arms! 2) Karnak is a leviathan that is comprised of three major temple enclosures, the grandest of which is the Precinct of Amun; it is large enough to house 10 great cathedrals. 3) Karnak covers over 100 acres, at its zenith during the reign of Ramses III it included 65 villages, 433 gardens, 421,662 heads of cattle, 2,395 km2 of fields, 46 building sites, 83 ships, as well as 81,322 workers and slaves!! Source: The Rough Guide to Egypt.

Luxor Temple and Karnak

Luxor Temple is a large Ancient Egyptian temple complex located on the east bank of the River Nile; it was founded in 1400 BCE during the New Kingdom.

The earliest parts of the temple still standing are the baroque chapels built by Hatshepsut, and later usurped by Tuthmosis III. However, it was largely built by Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BCE) who expanded on Hatshepsut’s shrine. Over the centuries additions were made by Tutankhamun, Rameses II, who built the entrance pylon, and the two obelisks – one of which is now at the centre of the Place de la Concorde in France – linked the Hatshepsut buildings with the main temple, and Alexander the Great. The Romans used it as a fortress.

The Karnak Temple Complex, on the other hand, is immensely difficult to describe, as Amelia Edwards, the 19th century writer and artist, best put it:

It is a place that has been much written about and often painted; but of which no writing and no art can convey more than a dwarfed and pallid impression… The scale is too vast; the effect too tremendous; the sense of one’s own dumbness, and littleness, and incapacity, too complete and crushing.

It was built over 1300 years; its core built during the 11th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, and virtually every Pharaoh from then on added to its glory, with the final development done by Philip III Arrhidaeus, he replaced the shrine of Thutmose III with a red-granite shrine. The Opet temple was the last important cult building to be constructed in the Karnak Complex.

The Theban Necropolis and the West Bank of Luxor

Lush green vegetation gives way to mountains and barren rocky valleys, this is the west bank of the Nile at Luxor, this is where Pharaohs, Kings, Queens, and nobles came to be immortalized within magnificent tombs cut into the heart of the mountains and the valleys.

First thing tourists see upon arriving to the west bank are the Colossi of Memnon, they loom 18m above the fields, and were at the gates of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple that was estimated to be even larger than Karnak. The colossi were severely damaged in 27 BCE and it caused one of them to “sing” at dawn, however at the orders of Septimus Severus in 199 CE, they were repaired, never to sing again.

Further from the Colossi, on the outskirts of the Valleys of the Kings and Queens, are several important sites: the recently opened Temple of Merneptah, one of Ramses II’s children, he succeeded his father and ruled for 10 years, the famous Israel Stele was found here. To the north of it is the Ramesseum, the mortuary temple of Ramses II, it lies in ruin mostly because of the bad choice of building location, a site that got inundated annually. Even further north from the Ramesseum lays the mortuary Temple of Seti I (1294-1279 BCE) near the village of Gurna Ta’rif, he died before it was finished and was completed by his son Ramses II.

To the south of the Temple of Merneptah is Madinet Habu, the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III, second only to Karnak in its size and complexity, and better preserved, it is best known as the source of the inscribed reliefs depicting the advent and defeat of the Sea Peoples during his reign.

A compilation of the glass and faience inlays depicting the traditional enemies of Ancient Egypt, found at/by the royal palace adjacent to the temple of Medinet Habu, from the reign of Ramesses III (1182-1151 B.C.E.) Representations are (in order L to R) a pair of Nubians, a Philistine, an Amorite, a Syrian and a Hittite. On display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The necropolis itself is too vast and complex, and trying to cover it all as well as the outer laying temples in one visit is virtually impossible; even limiting the visit to one or two sites is exhausting.

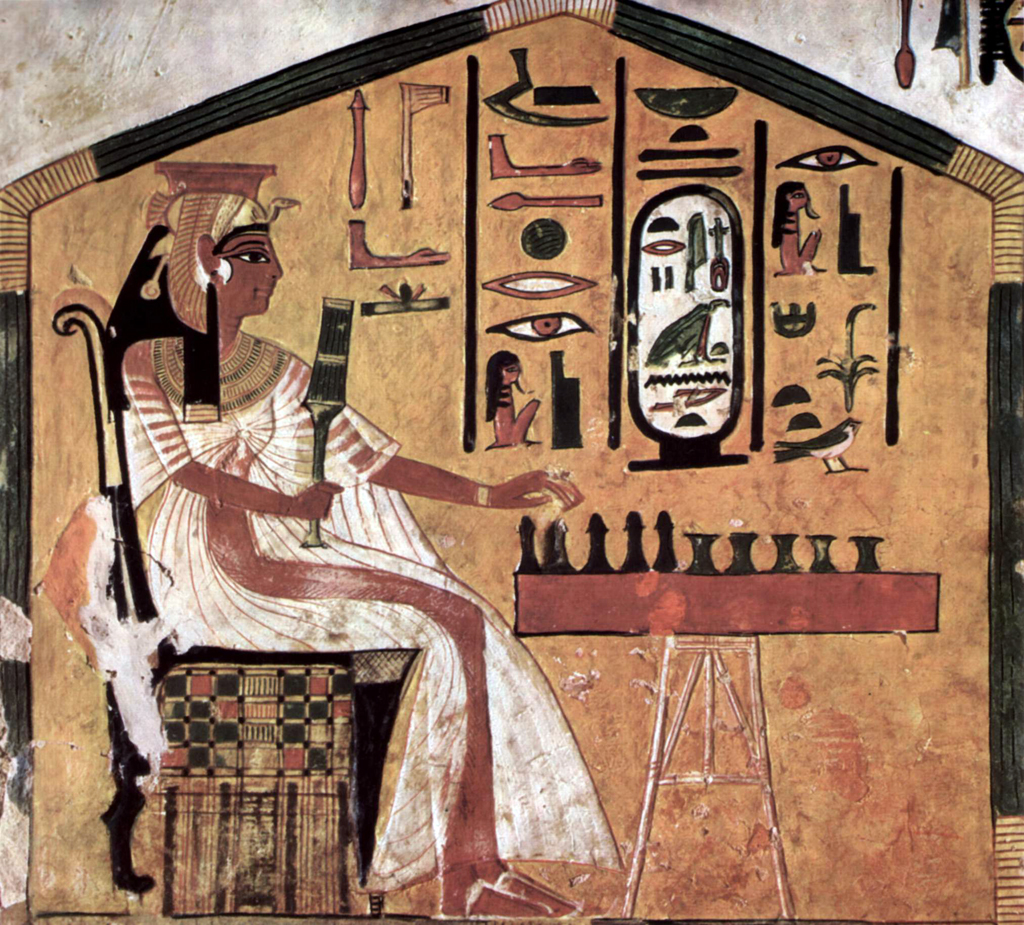

The grandest of the tombs are in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, where some of the most famous of Pharaohs are buried: Tutankhamun, Ramses III, Seti I, and Merneptah. Tickets to Tutankhamun’s tomb are sold separately from the other tombs. The Valley of the Queens is not just for the queens, the royal brood and some high officials are also buried here. At the moment only tombs no. 43, 44, 52, 55, and 66 are open. Tomb number 66 belongs to none other than Queen Nefertari, and due to the fragile state it is in, only small corporate or VIP groups are allowed to the tune of US$ 4,000.

Grave chamber of Nefertari, wife of Ramses II, Scene: The Queen Nefertari playing a game of Senet - the game of passing - possibly the oldest board game in the world.

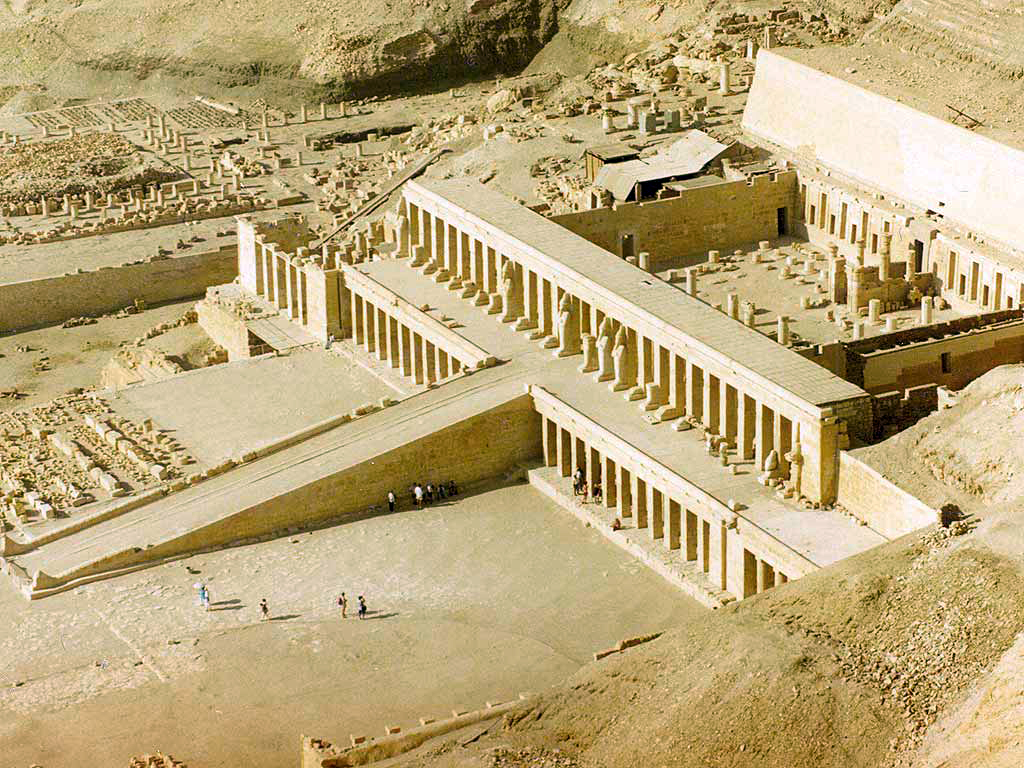

Al-Deir Al-Bahari, Hatshepsut’s awe-inspiring magnificent Mortuary Temple, is nothing short of breathtaking, dubbed by Hatshepsut as the Splendour of Splendours; one of its highlights is the Punt Colonnade, it depicts the Journey to the land of Punt – modern day Somalia – as it unfolded, from start to finish.

Deir Al-Madina, the Worker’s Village, housed the masons, painters, and sculptors, who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings; it has been excavated by archaeologists for most of the 20th century and at least 70 houses have been uncovered. However, only three tombs are currently open to the public: Tomb Inherka (no. 359), Tomb of Senndjem (no. 1), and Tomb of Peshedu (no. 3).

Another major site in the Theban Necropolis is the Tombs of the Nobles, they are the opposite of their royal counterparts in every way: they were left open and unguarded, they were not concealed deep underground, instead they were in the foothills overlooking their masters’ temples, and while the royal tombs were full of scenes of the afterlife, their tombs marvelled at everyday earthly life.

Armant and Esna

They were annexed to Luxor governorate in 2009 through a presidential decree, Armant sits on the site of the ancient Egyptian city of Iuny; known in Greek as Hermonthis, is located about 12 miles south of Thebes on the west bank of the Nile. It was an important Middle Kingdom town and the centre for the cult of Menthu the ancient Egyptian deity that was associated with raging bulls, strength and war. Of the temple dedicated to Menthu, only the remains of the pylon of Thutmose III are visible today.

Esna, known to the ancient Egyptians as Iunyt or Ta-senet; and to the Greeks as Latopolis, is located on the west bank of the Nile, about 55 km south of Luxor; all Nile cruises have to queue here to negotiate their way through the lock system. The Greeks named it in honour of the Nile Perch, Lates niloticus, the largest of the 52 species which inhabit the Nile, which was abundant in these stretches of the river in ancient times. Esna is home to the Temple of Khnum is remarkable for the beauty of its site and the magnificence of its architecture. It is built of red sandstone, and its portico consists of six rows of four columns each, with lotus-leaf capitals, all of which differ from each other. Restoration of the temple was began by Ptolemy III Euergetes, the restorer of so many temples in Upper Egypt, and over the years it was expanded and added to by Ptolemy V Epiphanes, Ptolemy VI Philometor, Ptolemy VIII Physcon, Emperor Claudius (41-54 CE), Emperor Vespasian, Emperor Geta, Emperor Caracalla (212 CE), and last but not least, Marcus Aurelius.

The other main point of interest in Esna is its lively tourist-oriented market, which fills a couple of streets leading inland from the corniche.

Trackbacks for this post