To the Ancient Egyptians it was known as the Red Land, the Land of Osiris, where the dead went. And up until they realised the existence of human settlements in it, they paid it almost no attention at all, beyond using it as burial grounds.

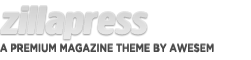

The Western Desert of Egypt – sometimes strangely called the Libyan Desert – is part of the Sahara that lies in Egypt. It covers almost two thirds of Egypt, at a whooping 681,000 km2. Over millennia it turned from lush savannah to a barren desert due to geological changes and overgrazing by Stone Age pastoralists.

There are wonders in the Western Desert that have finally gained the spotlight in eco tourism; there are the White and Black deserts, the Great Sand Sea, Gelf Kebeir and Jebel Uwaynat, and the Valley of the Whales among many. This is Egypt’s final frontier.

“There are deserts and there are deserts. But the Western (Libyan) Desert, a vast expanse that starts at the western banks of the Nile and continues well into Libya, is the desert of deserts.” Ralph Bagnold, Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World.

Al-Fayoum

Located about 81 miles (130km) south west of Cairo, its name is derived from Coptic Payoum, meaning the Sea or the Lake, which in turn comes from late Egyptian pA y-m of the same meaning, a reference to the nearby Lake Moeris, also known as Lake Qaroun.

Unfortunately, because of its proximity to Cairo and Giza, the city of Fayoum itself is not really an urban centre or rural centre either; it’s a bit chaotic with a bit of an identity crisis, with all of Greater Cairo’s drawbacks and none of its charm. It has, however, several sites that are worth the trip, and a long with Bahariya Oasis in Giza, it serves as a starting point for deep desert safari exploration.

Al-Fayoum has always been linked to the Nile Valley since antiquity; it came into prominence during the reign of King Senusert I, second king of the XII Dynasty, who saw in Fayoum as something more than hunting grounds. After the XII Dynasty, the lure of Al Fayoum declined not to be revived until the Ptolemies.

Lahun Pyramid, Hawara Pyramid, and the Fayoum Portraits

Entering Al- Fayoum you pass the Lahun and Hawara pyramids, the former built by King Senusert II employing newer techniques than from the pyramids of Giza devised by the architect Anupy. The Hawara pyramid was built by Amnemhat III, his mortuary temple may have been known to Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Pliny, and Strabo as the “Labyrinth”, the fabled building was said to have over 3000 chambers hewn from a single rock according to Herodotus; Strabo praised it as a wonder of the world. The pyramid itself contained some of the most complex security features of any found in Egypt and is perhaps the only one to come close to the sort of tricks Hollywood associates with such structures. Sources: Wikipedia, The Rough Guide to Egypt.

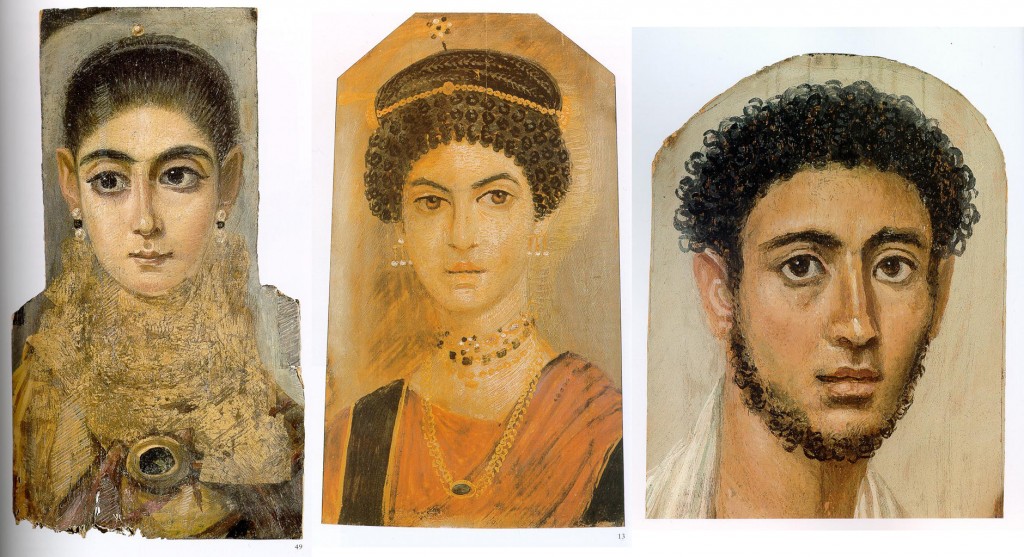

Fayoum Mummy Portraits, L to R: Louvre, Paris; Royal Museum of Scotland, Scotland; Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich. Wikimedia Commons.

The Fayoum Mummy Portraits refer mostly to the style than the geographical location of the portraits, although the majority of them were indeed discovered in Fayoum. They are famed with their brilliant naturalistic style. They date back to the Roman times, specifically from the late 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. It is estimated that there are about 900 mummy portraits are known at present scattered in several prestigious museums around the world.

The Seven Waterwheels, the Obelisk of Senusert I, and ‘Ain Al-Siliyn

The Seven Waterwheels date back to the Ptolemies, they are found about three kilometres to the north of the city of Fayoum along the right bank of Bahr Sinnuris. Entering or leaving the town you pass the 13 metre high Obelisk of Senusert I, it is the only obelisk in Egypt that has a rounded tip.

‘Ain Al-Siliyn is a natural spring halfway between Fayoum city and Lake Qaroun with traces of titanium that is supposed to be good for the blood pressure; that is somewhat in dispute, but there is an orchard and waterwheel – Fayoum is full of them – and it has its charm, as long as you don’t visit on a Friday.

Kom Oshim, Qasr Al-Sagha, Dimeh Al-Siba’, and Widan Al-Faras

30km from Fayoum city to the north, coming in from Cairo, the first thing you see is the remains of the ancient Greco-Roman settlement of Kom Oshim/Karanis. In ancient times it was on the banks of Lake Moeris, but as the lake receded, the ruins are surrounded by nothing but desert as far as the eye can see. Karanis was the cult centre for the crocodile deity Sobek, and among the ruins of the city, there are two temples that are better preserved, one dedicated to the local crocodile deities and the other to Sobek, Jupiter, Zeus, Amun, and Serapis.

Further north of the Lake, a 4WD and a love of the desert and you can get to several remote sites: Qasr Al-Sagha, Dimeh Al-Siba’, and Widan Al-Faras. These sites are best visited accompanied by a guide, as the tracks leading to them are not always very clear.

Qasr Al-Sagha (Palace of the Jewellers) is a small Middle Kingdom temple with seven shrines and fantastic views of Jebel Qatrani.

Dimeh Al-Siba’ (Dimeh of the Lions) is around 8km to the south of Qasr Al-Sagha, it was the site of a Ptolemaic town known as Soknopaiou Nesos. Its Greek name means ‘Island of the Crocodile-god’. The ruins and the city wall are visible from a distance at 10m high and 5m thick in places. It once sat on the banks of the lake Qaroun, as the lake receded; however, the town was no longer sustainable. The lake now lies 11km away.

Part of what remains of the ancient town of Crocodilopolis at Karanis, L: men's bath, R: an enclosed sunken women's bath.

The Old Kingdom quarries of Widan Al-Faras are where the basalt used for pots and statues came from, Widan Al-Faras itself is a mountain extruded from the Jebel Qatrani Formation, which, in turn, is a palaeontological formation located that dates to the Eocene-Oligocene period and is very rich in fossils and is covered in a thick layer of black basalt.

The quarry road is considered to be the world’s oldest paved road, dating back 4000 years and made with stones and chunks of fossilized wood. Source: The Rough Guide to Egypt.

Qasr Qaroun, Madinet Madi, and Tunis

Sitting within the ruins of the ancient Ptolemaic frontier town of Dionysias are the two temples that make up Qasr Qarun. The town itself was founded in the 3rd century BCE, only to be abandoned in the 4th century CE due to the recession of Lake Qaroun, now a 45 minute walk away. To the west of the temples there are the remains of the mudbrick fortress built by the Emperor Diocletian to protect the town against Bedouin tribes invading from the west. Sources: Egyptian Monuments, The Rough Guide to Egypt.

En route to Madinet Madi to the south of Qasr Qaroun you will find the village of Tunis, picturesque lakeside village overlooking Lake Qaroun. The area was discovered in the sixties by two famous Egyptian poets of the 20th century and has since evolved into an artists’ colony with pottery schools and houses built in Bedouin style with local material and an eco lodge called Zad Al-Mosafer – Provisions of the Traveller. The foremost residents of the village are two of the world’s leading potters, Evelyne Porret and Michel Pastore. Evelyne established the first pottery school in the village modelled on Egyptian artist Ramses Wissa Wassef’s school weaving school in Al-Harraniya in Giza.

Further south, as you move on from Tunis, is Madinet Madi – City of the Past. The temple, one of the most isolated and romantic sites of the Fayoum, was started during the reign of Amnemhat III and completed by his son Amenemhat IV of the XII Dynasty. In Graeco-Roman times it was known as ‘Narmouthis’. Excavators have discovered two separate towns at the site, but today the main monument at Medinet Madi is the small temple dedicated to Sobek, Horus and the serpent-goddess Renenutet. Source: Egyptian Monuments.

Lake Qaroun, Wadi Al-Rayan and Wadi Al-Hitan Protectorates

Lake Qaroun, Wadi Al-Rayan, and Wadi Al-Hitan have been declared protectorates in 1989. Wadi Al-Hitan is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Lake Qaroun is what remains of the ancient Lake Moeris. People have debated the name “Qaroun” for a while, especially when daydreaming about immense treasures that might be buried deep beneath the lake. The reason for that is the name itself; it is named after a Jew who was a contemporary of Moses (عليه السلام) during his time in Egypt, who, according to the Quran, not only betray his people, but also was so wealthy that the keys to his vaults required around nine strong men to carry them. In the Quran as a punishment for his arrogance the ground opened up and swallowed him and his palace and vaults, however, we were never told where that took place. But that never deter the daydreamers.

In ancient times, the lake was a freshwater lake and covered a much larger area than the mere 1155 square kilometres it covers today, but by the end of the 19th century it has become too salty for the freshwater fish living in it, and by 1970 several marine species were introduced.

The Auberge du Lac-Fayoum was once the hunting lodge of King Farouk, it was also where Allied and Arab leaders met to carve up the Middle East after WWII. The lake itself has a prolific birdlife; 88 species, including flamingos.

Stretching over an area of 1759 km2, Wadi Al-Rayan consists of an upper lake and a lower lake with waterfalls in between. There are also four sulphur springs at the southern side of the lower lake, and long dense mobile sand dunes. The area is home to 15 species of desert plants, 15 types of wild mammals, including the world’s few remaining populations of the endangered Slender-horned gazelle, 16 species of reptiles, and over 100 species of resident and migrating birds.

Wadi Al-Hitan, Valley of the Whales, is technically part of the Wadi Al-Rayan protectorate, but it is worlds apart from it. It is a paleontological site and it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in July 2005 for its hundreds of fossils of some of the earliest forms of whale, the archaeoceti (a now extinct sub-order of whales). No other place in the world yields the number, concentration and quality of such fossils, as is their accessibility and setting in an attractive and protected landscape. Sources: Wikipedia, World Heritage Centre.

Wadi Al-Hitan is a natural environment for animals threatened with extinction like the white deer, Egyptian deer, sand fox, wolf and rare migrating birds like the shahin falcon, deer falcon, and free falcon among others.

Al-Wadi Al-Jadeed (New Valley)

West of the Nile is the beautiful barren, magnificent, and humbling Western Desert. Not completely void of life though, there are several pockets of life and vegetation in the middle of this wasteland. The area was named so by Jamal Abdul Nasser in 1958 when he initiated a project to cultivate the Western Desert and have people move there to reduce the pressure on the Nile valley. It remains to this day the largest governorate in Egypt and the least populated.

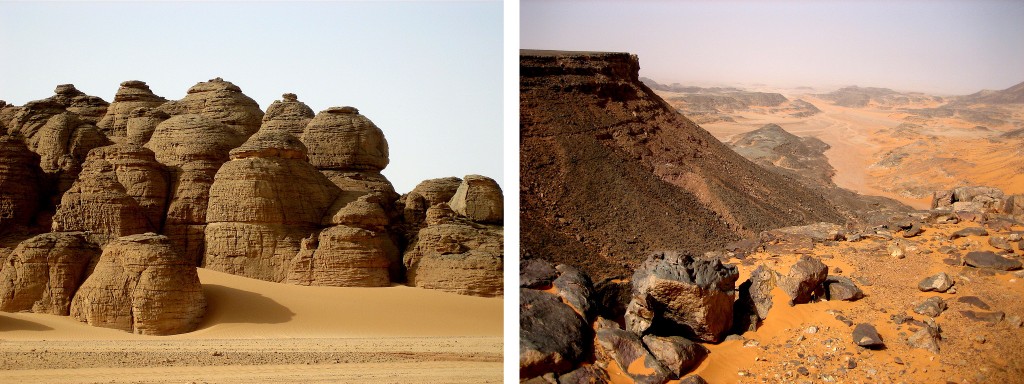

In ancient times, the Western Desert was once savannah, akin to the African plains, with a myriad of wildlife; giraffes, lions, and elephants once called this place home. Climate change gradually led to the desertification of this lush savannah, and turned it into the arid inhospitable land we know today.

Farafra Oasis

Heading south from Bahariya Oasis, the road to Farafra Oasis is not a disappointment. The landscape dramatically changes from the unearthly volcanic mounds of the Black Desert to the snow-like ergs and mushroom formations of the White Desert.

The White Desert Protectorate was established in 2002 and it covers an area of 300 km2, and it is a must see on any desert safari. At its entrance there’s Crystal Mountain, a ridge that is entirely composed of quartz crystals.

Another attraction in Farafra is the Jara Cave with its 9,000 year old drawings, a massive cave that contains gorgeous prehistoric rock art. Most of the engravings depict big game hunts and everyday life. It was discovered by Gerhard Rohlfs in 1873, only to be forgotten and rediscovered again by Carlo Bergmann in 1991. Sources: Egypt Travel, The Rough Guide to Egypt.

Other attractions include Badr Museum, a showcase for traditional oasis life; Qasr Al-Farafra, Farafra’s only town with its mud-brick houses and Roman fortress; and the Bir Sitta Hot Springs, Well Number Six, a sulphurous hot spring 6km north of Al Qasr.

Dakhla Oasis

Around 250km southeast of Farafra is Dakhla Oasis. About 75,000 people live in 14 settlements spread in and around the oasis itself, supported by more than 520 wells, with an abundance of lush fields, orchards, and groves. It does not lack in sites, there are Pharaonic, Roman, Coptic and Medieval Islamic monuments that can be explored around the main villages.

The main base for travellers to Dakhla is the town of Mut. The old town is still at its centre with its old windowless houses and winding passages that are an adventure on their own. Around Mut there are several sites to explore and several hot springs to relax in. North of Mut is the old village of Al-Qasr, renowned with its old town. An international team from the Dakhla Oasis Project and the SCA has been carrying out painstaking restoration of the town for the last 30 years or so.

Close to Al-Qasr you can find the Muzawaka Tombs, they’ve under restoration for years, and yet further off the beaten path is Deir El-Hagar – Stone Monastery, an ancient Roman temple dedicated to the Theban Triad and the oasis deity Seth.

To the east of Mut on the road to Kharga Oasis you pass through several settlements with history stretching back in time to Roman and Pharaonic times. Asmant Al-Khorab – Asmant the Ruined, the local name for the ruins of Kellis, a Roman and Coptic settlement. The site is off limits due to excavations. Further down the road past several smaller settlements and 10 km off the highway at the village of Teneida there are some rock inscriptions including giraffes, ostriches, camels and hunters.

Kharga Oasis

189 km east of Dakhla is Kharga Oasis, the capital of Al-Wadi Al-Jadeed, and the one oasis with a large collection of ancient monuments and sites. The town of Kharga itself is very much faceless, having turned its back on traditional oasis life for dreams of modernity back in the 1960s.

The old Christian Coptic necropolis at Al-Bagawat in the Kharga Oasis (3-7th century CE.), Western Desert. Wikimedia Commons..

Taking the town of Kharga itself as a starting point, there are plenty of sites and excursions to the north and to the south on the road to Baris Oasis. To the north of Kharga there are the Temple of Hibis, the Bagawat Necropolis, Deir Al-Kashef, named after the local Mameluke tax collector, and the ruins of the Temple of Nadura. Other sites are less accessible and require a guide and a 4WD, include a marvel of Roman engineering, a grand underground aqueduct at Ain Umm Dabadib. Source: The Rough Guide to Egypt.

To the south of Kharga on the road to Baris, there are to chief sites that can be visited: Qasr Al-Ghweita – Palace of the Beautiful, a well preserved mud-brick Roman fortress enclosing a sandstone temple from the late period, once at the centre of a thriving agricultural community, now mostly surrounded by sand. The other site is Qasr Al-Zayan, another temple enclosed within a mud-brick fortress. Sources: The Rough Guide to Egypt, Lonely Planet Egypt Travel Guide.

Baris Oasis

Named after the French capital, Baris (pronounced Barees), doesn’t offer much to travellers beyond Qasr Al-Dush about 23 km to the south of the main town; the ruins of the ancient town of Kysis and its hilltop fortress, and the impressive Temple of Dush, built by Domitian and completed in 177 CE by Emperors Hadrian and Trajan, the temple was dedicated to Isis and Serapis, and is renowned to have been partially covered in gold. Sources: The Rough Guide to Egypt, Lonely Planet Egypt Travel Guide.

Al-Gilf Al-Kabir National Park

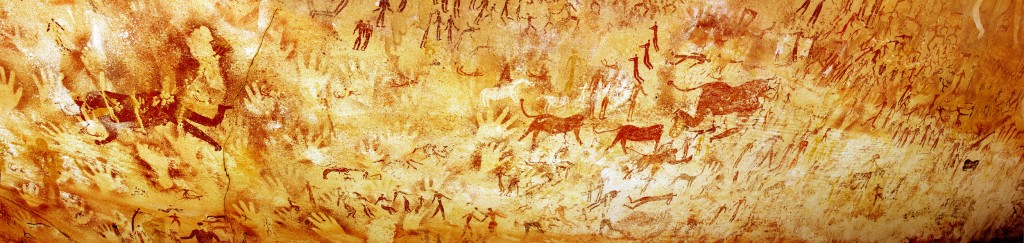

This is the final frontier of Egypt, the closest environment on earth to the surface of Mars. In ancient times the area was inhabited by cattle pastoralist cultures that left thousands of engravings and rock art depicting giraffes, ostriches, lions and cattle, as well as people hunting and swimming. This lifestyle came to an end when the climate changed dramatically, shifting savannah into arid desert around 5,000 BCE, making it a hostile inhospitable place. The closest water source is almost 500km away at Bir Tarafawi.

In 2007 the Gilf Kebir National Park was established, with a total area of 48,533 km2, at its heart is the Gilf Kebir Plateau a massif twice the size of Corsica, dissected by massive wadis (valleys). About 150km south of Gilf Kebir Plateau is Jebel Uewinat, a 1,934 metres high massif with a wealth of geological formations, rock paintings, and petroglyphs. Lastly, the Great Sand Sea; a complex chain of dunes that are among the largest of its kind in the world, it stretches for over 650km from Siwa Oasis to the Gilf Kebir Plateau. Source: Gilf Kebir National Park, by Alberto Siliotti.

The first to discover the Gilf Kebir “Great Barrier” Plateau was Prince Kamal Al-Din Hussein, heir to the Egyptian throne, in 1926. What followed was a flurry of exploration carried out by a handful of men from different nationalities who dedicated their lives to this region. The area later became an important stage of reconnaissance and intrigue during WWII. Several legends were born here: László Almásy, the real English Patient; and the famous Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) founded by Major Ralph Alger Bagnold, one of the original group of explorers of the Gilf.

There are several must-sees in the area, the most famous of which lies in Wadi Sura, with the Cave of the Swimmers and Cave of the Archers, discovered by Almásy in 1933, and the Foggini-Mestikawi Cave, dubbed the ‘Sistine Chapel of Prehistory’ due its 100s of perfectly preserved rock paintings, it was discovered by chance in 2002 by the Italian Massimo and Jacopo Foggini during an exploration with Western Desert veteran Colonel Ahmed Mestikawi.

Jebel Uweinat, Wind Streaks. By NASA/Crew member of Expedition 4. Identification: Mission: ISS004 Roll: E Frame: 13542 Mission ID on the Film or image: ISS004.

Jebel Uweinat – Mountain of Small Springs – was discovered and named by Egyptian adventurer Ahmed Hassanein Bey who, in 1923, crossed the entire Western Desert with a camel caravan starting from the Mediterranean coast heading south for 2,200 miles finally reaching Jebel Uweinat. Extending into Jebel Uweinat is Karkur Talh, Acacia Valley, an open air museum with over 4,000 rock art sites.

Tutankhamun's pectoral features a scarab carved from Libyan Desert Silica Glass. By Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons.

The first European to traverse the Great Sand Sea was German explorer, Gerhard Rohlfs in 1874 with a caravan of 17 camels; it took a total of 36 days. It is one of the largest expanses of sand in the world, at 72,000 km2; it is roughly the size of Ireland. It also holds on the greatest mysteries of the Sahara: Libyan Glass, it was discovered in 1932 by English explorer, Patrick Clayton. However, a study of Tutankhamen’s pectoral in 1998 revealed that the glass scarab adorning it was in fact made with Libyan Desert Silica Glass.

The section regarding Al-Gilf Al-Kebir National Park is but a small summary of the very thoroughly detailed guide: Gilf Kebir National Park, by Alberto Siliotti. If you plan a visit to the park, this is one item that you cannot do without.

Trackbacks for this post